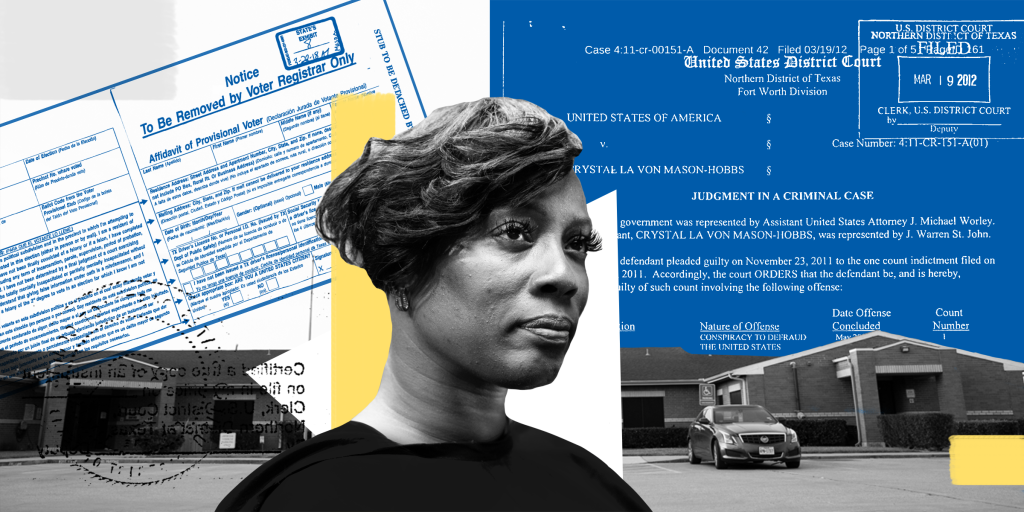

Crystal Mason thought she had the right to vote. Texas sentenced her to five years in prison for trying.

Crystal Mason, an African American mother of three from Texas, did her civic duty and filled out a provisional* ballot in the 2016 election. Mason was on federal supervised release, for offenders recently released from prison, who, unbeknownst to her, were barred from voting. A judge sentenced her to five years imprisonment, and the ACLU is suing for her release.

Go here to sign a petition to support her release and protest the unfair, racist punishment https://tinyurl.com/MasonVotes, an excellent example of how the American justice system over-incarcerates, and picks on people who are least able to defend themselves.

After release from prison, Mason had started her own business while holding a full-time job, going to school and taking care of her three children, and four additional children. When she went back in prison, others had to take care of the seven children and teenagers, placing a burden on social services and others.

Contrast Mason’s story with a white woman in Iowa, Terri Lynn Rote, convicted of voter fraud after purposely trying to cast a ballot for Trump twice, who was sentenced to 2 years probation and a $750 fine.

In 2019, a white Republican justice of the peace in Tarrant County, Texas, pled guilty to submitting fake signatures to secure a place on a primary ballot and was sentenced to five years’ probation.

But Mason, a black woman who successfully rebuilt her life after prison, is in prison for five years committing an honest harmless mistake, and a ballot that wasn’t even counted. Please sign the petition now https://tinyurl.com/MasonVotes.

For details of Mason’s trial, visit the ACLU website.

*A provisional ballot on Election Day is used to record a vote when there are questions about a given voter’s eligibility that must be resolved before the vote can count.

U.S. sends the ‘worst of the worst’ to ADX super-max prison in Colorado, with poor outcomes

The U.S. sends ‘the worst of the worst’ to ADX. Here’s what happens when they get out from VICE News, Aug. 28, 2019

If you’re not signed up for this newsletter, change that by clicking this link.

The federal prison known as “The Alcatraz of the Rockies” or ADX is in the middle of nowhere, about a two-hour drive south of Denver. It houses many of the most notorious and violent criminals convicted in the United States, including terrorists, spies, mass murderers, and drug kingpins like El Chapo.

Of the federal prison system’s approximately 150,000 inmates, the 375 or so at ADX are often described as “the worst of the worst.” Every prisoner is housed in solitary confinement, most for 22 or 23 hours a day, typically in a 7-by-12 concrete cell.

But while some ADX prisoners are high-profile criminals serving life sentences, others are relative unknowns who are eventually released. And despite multiple warnings and violent incidents, the Bureau of Prisons has sent severely mentally ill inmates home from ADX with virtually no preparation for life on the outside.

One of those inmates was Jabbar Currence, who spent nearly 11 years at ADX. Three days after he was released from federal custody in February, Currence sexually assaulted a woman in a Virginia park. VICE News spoke with Currence and 10 other former ADX prisoners. Each had a different story, but virtually all of them described receiving little or no preparation for returning to society after years of brutal isolation.

At least four besides Currence have been either accused or convicted of serious felonies after being released from ADX. It’s unclear exactly how many prisoners have been let out of ADX over the years and how many of those have gone on to commit more crimes, but independent inspectors found that around 50 inmates at ADX were scheduled to be released from 2017 to 2020.

Read more from Keegan Hamilton on VICENews.com.

What happens to inmates after solitary confinement

The problems with ADX reflect a nationwide issue with solitary confinement. An estimated 61,000 people are held in isolation in prisons and jails across the U.S., and it is now often the de facto way to deal with unruly inmates and those with mental illness. Many jurisdictions have no rules in place to ensure that inmates are not released directly from solitary to the streets.

Numerous studies suggest that prisoners who spend time in solitary are more likely to reoffend than those who don’t.

“It made me not want to be around people,” Currence told us. “It made me more angry. It made me more resentful. It made me more thoughtful. I think it made me more of a predator. Well, not predator in the sense that — it just made me angry. Real angry.”

Watch our segment, which originally aired on VICE News Tonight on HBO.

“Leaving there, I was 10 times more violent”

Tim Tuttamore returned to his hometown in Ohio last November after an 18-year prison sentence with 12 served at ADX. In prison, he called himself an “independent skinhead,” and he was sent to ADX because he repeatedly attacked other inmates and was considered a leader among white supremacist gangs at another high-security penitentiary.

He has a long history of mental illness, which he says was made worse by his years in isolation at ADX.

“I went there as a violent person, but leaving there, I was 10 times more violent,” he said. “There’s no rehabilitation. None. They got all these stupid little courses you take. They’re meaningless. It doesn’t help you. It doesn’t help when you get out of prison.”

Treatment not jails

by Lois Ahrens

Published: 8/18/2019 by the Daily Hampshire Gazette

Michael Ashe, the longtime former sheriff of Hampden County, was an excellent salesman. He sold legislators on the idea that he could see into the future, and the future meant more incarceration.

Legislators believed him and taxpayers footed the bill for a jail in Ludlow big enough to cage 1,800 men. His successor, Sheriff Nick Cocchi, has a problem. Ashe’s prediction has not come true.

As of July 1, the Ludlow jail is incarcerating 421 pretrial men and 273 sentenced men, according to information provided by an attorney for the jail in response to a public records request. Sixty-eight men are jailed under Section 35, which allows the state to jail men who are civilly committed for “treatment” for substance abuse disorder. That is a total of 762 men; way under the number Cocchi needs to justify keeping all of his big jail open.

If bail reform happened and real alternatives to incarceration were implemented, what would Cocchi do? One alternative is jailing people under Section 35. Another option Cocchi is exploring, according to a WBUR report, is a lucrative agreement — at least $91 a day per person — with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to lock up undocumented immigrants.

In 2017, it cost taxpayers $77,729,229 a year to run Hampden County jails, according to budget documents for the jail. The majority of women and men incarcerated there are being held “pretrial,” that is they are mostly too poor to make bail. They have been convicted of nothing. It costs $100,000-plus annually per person to jail someone there. If $77 million is not enough, Cocchi has just persuaded legislators to give him $1 million more to support “treatment” at the jail.

Cocchi maintains that he is locking up men with substance use disorder because he is the only one who is compassionate enough to do it.

No matter that this flies in the face of what health and mental health practitioners believe — that people with substance use disorder are not criminals and that stigmatizing and criminalizing people runs counter to best practices.

No matter that on July 1, the majority of state commissioners who studied Section 35 for a year voted to recommend that the state be prohibited from sending people to jails and prisons for addiction treatment.

One thing is true, Cocchi has a lot of empty cells and a lot of correctional staff, and has hired some treatment providers. He is able to do this because we have invested billions of our tax dollars in building and funding jails.

And, as long as millions are poured into jails, they will not go to community-based, community-run treatment on demand. Think about what kinds of quality services and programs could be purchased for $100,000 per person. If these same choices are repeated, jail for people with substance use disorder will be the default. And if Cocchi has his way, jailing people under Section 35 will not only expand in his jail, it will open the doors around the state to other sheriffs who also have empty cells.

Massachusetts is an outlier. We are the only state that civilly commits people to jail only because they are living with substance use disorder. Now is the time to end it. Let’s invest in treatment not jails.

Lois Ahrens is the founding director of The Real Cost of Prisons Project, a national organization based in Northampton. For more information, find The Real Cost of Prisons Project on Facebook and at www.realcostofprisons.org.

https://www.gazettenet.com/Guest-column-Lois-Ahrens-27779474

Baker undermining solitary confinement reform

By Margaret Monsell

Last year’s criminal justice reform law tried to nudge the state toward a more humane policy on solitary confinement in the state’s prisons and jails by adding due process protections for all prisoners confined to their cells for more than 22 hours a day and creating a 12-member Restrictive Housing Oversight Committee consisting of mental health and social work professionals as well as corrections personnel to conduct an annual study of solitary confinement practices, including recommendations on ways to minimize its use.

The Baker administration, deeply unenthusiastic about this initiative, is using the regulatory process to throttle it. In March, the Department of Correction sidestepped the new due process protections by way of regulations confining some prisoners to their cells for 21 hours a day instead of the 22 hours referenced in the statute. Problem largely solved.

And in mid-June, the Department of Correction issued regulations governing the Restrictive Housing Oversight Committee that will certainly impair its ability to carry out its mission. Despite statutory language giving committee members “access to all correctional institutions,” the regulations require advance approval from the institution superintendent before any visit, prohibit a quorum or more of committee members from visiting the same institution at the same time, and apply all the rules governing visitation generally to committee members as well, making them, for example, subject to searches for weapons and contraband and to having their visits terminated at the discretion of corrections staff.

The committee must also obtain a written release from every inmate before reviewing any medical, criminal history, or other information the institution has about that inmate. While this requirement may serve the inmates’ privacy interests, it also provides corrections staff with a list of the inmates who have cooperated with the committee’s inquiries, intelligence that inmates might reasonably believe would lead to retaliatory punishment.

In addition to these constraints on the ability of committee members to gather information, the regulations also forbid them from making “any statement(s) to the public or the press about any matters pending before the Committee, unless approved by the Chair of the Committee to do so” (the chair of the committee is the governor’s secretary of public safety).

What constitutes a “matter pending before the Committee” remains undefined in the regulations, but presumably it includes the subjects the committee is required to address in its annual report, such as the criteria for placing an inmate in restrictive housing and the effect of restrictive housing on prison safety. In the absence of the chair’s approval, members would be unable to share their experiences and findings with anyone, including the Legislature, which established the committee for the purpose of its own edification.

The Department of Correction put these regulations forward on an emergency basis, which means that they’re effective immediately and that the agency may dispense with the usual period between the announcement of a proposed new regulation and its adoption, during which time it is required to receive and consider public comments. (The solitary confinement regulations issued in March were also emergency regulations).

Although they’re effective immediately, emergency regulations are of limited duration. These expire at the end of August. Maybe before then, the Legislature, the public, and the press can convince the Baker administration that, unlike these emergency regulations, permanent ones must reflect the fact that solitary confinement policy is not exclusively an executive branch prerogative.

Margaret Monsell is an attorney practicing in the Boston area.

Shine a light on the fine print in the MA 2020 buget for yyour state legislators

| Susan Tordella <emit.susan@gmail.com> | Thu, May 9, 2:14 PM (6 days ago) | ||

| to EMIT-Mass |

Buried in the House version of Gov. Baker’s budget is a requirement to keep all existing corrections facilities open in the next fiscal year.

The Mass DOC [Department of Corrections] headcount is down by nearly one-fourth since 2010, when the DOC reported 11,429 in their care, compared to the latest headcount of 8,700. The DOC and/or corrections officers union must be anticipating a logical proposal to close one or more prisons.

THE ASK: Please contact your state representative and senator to bring to their attention this scurilous requirement to block the closure of prisons. It’s important for both sides of the Statehouse to be aware of this because it re-emerge in the Conference Committee, when three representatives and three senators work out a compromise between the two versions of the budget.

Closing prisons makes sense, economically and for the health of incarcerated people. The two oldest facilities, Norfolk and Concord, were built in the 1800s, and Norfolk has notorious problems with mold and clean water.

If there’s going to be a decision made about closing prisons, we demand that it be made through a public discussion and democratic process.

Find your state rep and senator HERE, then save the information in your phone or computer for future contact. Feel free to copy and paste any part of this alert.

Background information

In addition to closing prisons, the DOC needs to transition more people to lower security levels, which is more economical. The higher the security level, the more expensive the staff expenditures. A lower security environment gives incarcerated people a better transition to freedom, and the opportunity to work in the community. The Council of State Government 2017 report recommended the DOC assign more people to minimum security prisons.

We conjecture that the DOC and/or possibly the corrections officers union may be behind this back-room maneuver, for many reasons. A mandate to keep all facilities open could possibly be: to maintain job security; to avoid the massive effort required to close a prison and re-assign people; and from the DOC perspective, for the security and safety of staff and those incarcerated. “Security” is the standard shield the DOC hides behind to avoid changes and improvements.

To see this in print, go to:House Version of Gov. Baker’s Budget, page 148, line 8900-0001 states:”For the operation of the department of correction, … [go to LINE 8]provided futher, that correctional facilities that were active in fiscal year 2019 shall remain open in fiscal year 2020 to maximize bed capacity and re-entry capability.”

The DOC is asking for $677,073,942 to run the DOC in FY 2020, a number that goes up exponentially every year.

We must hold the DOC accountable to: make open decisions about prison closures; spend wisely; offer more programs; and to classify as many people in their care to minimum security institutions.

The Case For Closing Prisons in Massachusetts If not now, WHEN ?

Crime rates and prison populations are dropping at a steady rate in Massachusetts due to many factors. Even larger cities like Boston and Worcester are reporting loweer crime rates.

The same is true of the prison population — which continues to drop. In 2010 the Massachusetts Department of Corrections [DOC] reported 11,429 men and women in custody. By 2018, that number dropped to 9,207 of which only 8,044 are sentenced for a crime.

The latest 2019 figures have not been released, but it is estimated to have dropped even more. This can be due to action by the courts, more alternative sentences that avoid prison, and more district attorneys who understand crimes that are related to substance abuse disorders.

The facts are clear, that in a good economy where crime is dropping and incarceration is dropping, we have to start talking about closing prisons.

With the 2020 State budget about to be decided, the proposed House Budget calls for $677,073,942 for the DOC. Gov. Baker is calling for even more. With some 8,000 incarcerated people, that will equate to more than $80,000 per inmate for one year of incarceration.

The DOC has one of the highest payrolls in the state with many corrections officers doubling their salaries with overtime. In 2018 the overtime account for corrections officers exceeded $32,000,000.

To stop this outflow of our tax dollars, it is time to think of closing prisons. Each prison requires a physical location, an administrative staff, officers, and overhead.

MCI Concord, one of the oldest prisons in the state, would be an excellent first choice to close. According to the DOC, MCI Concord housed 1,324 inmates in 2013. In 2018, that number dropped to only 613.

In 2017, the DOC stated in its facility brochure that it cost some $69,000 for each of the 613 inmates. Compare this to MCI Norfolk where costs was only $46,000 or Gardner NCCI, where the cost was $52,000 per year, per person. For only 613 inmates, as the new numbers may show, Concord MCI needs to close. The buildings are old and some are not usable because of mold and other problems.

MCI Concord is in a prime location and is assessed by the Town of Concord for nearly $40,000,000. In this hot real estate market, this prime property could sell for more.

When we start to close prisons, we can move incarcerated people to other locations. The recent evaluation by the Council of State Governments advised that the DOC assigns people at too high of a custody level, which requires higher staffing levels. More minimum and pre-release facilities could be opened with the money saved by closing a major prison.

The prison education could benefit because for every dollar spent on prison education, five dollars is saved on recidivism. The DOC reports there are nearly 4,000 people on a waiting list for HiSET [High School Equivalency Test] and vocational education. This is a disgrace. We need to make programs and education available to all people in the care of the DOC within six months of coming to prison — or sooner.

This can be achieved by better utilizing technology to educate with tablets that are already in use in the prisons. Former gym space or other areas can be converted into classrooms. When incarcerated people are ready to move to minimum or pre-release, they can work inside or outside the prison to better prepare to go home. The money saved on closing prisons will help the remaining ones gain access to programs, which now have long waiting lists.

There are nearly 3,500 corrections officers who supervise 8,000 sentenced people. Unlike some other states where officers run programs, Massachusetts employs officers primarily for security. With a thriving economy, now is the time to talk about closing prisons and increasing programming.

We taxpayers work hard to support our state, and deserve to see the money spent wisely. None of us would want a doctor who refuses to cure us just so he can continue to bill us for medical services. None of us would want our children with a teacher who fails her students just so that they return next year so she has a job.

In the private sector, jobs are changed all the time and facilities are closed and sold. Even teachers and doctors can be subjected to downsizing. There should be no guarantee of a job when it is no longer needed because taxpayers deserve better use of taxes. It is estimated that the numbers in prison will continue to drop and prisons will become more vacant.

We owe it to those in prison to make changes to save tax dollars and still provide a better experience where prison can actually educate and help those who are sent there. Let’s get ready to start closing prisons because the data is on our side. This is a subject that needs to be addressed and, if not now, when?

—Submitted by a person who has a family member in prison

Yet cash bail persists in MA

Massachusetts judges and prosecutors find it difficult to imagine there are people who cannot and do not have $100 to $500 cash to post for bail. Despite the Brangen decision, which prohibits imposition of unaffoardable cash bail upon “indigents,” the Mass Bail Fund still reports it provides assistance for people without means.

| Art and article courtesy of the New York Times |

Unable to Post Bail? You Will Pay for That for Many Years

by Seema Jayachandran, The New York Times, March 1, 2019 CreditImage

Cash bail favors the rich, who can pay it and go home, while poorer people are frequently forced to remain in jail while they await trial.

That fact alone helps to explain why cash bail has been eliminated or restricted in California, New Jersey and Arizona, and appears to be on the way out in a number of other places, including New York.

But two new studies in economic journals show that inequities in the cash-bail system lead to more long-lasting and pernicious consequences.

In itself, an inability to pay bail after being arrested makes it more likely that you will be convicted of that offense, according to a study published last year in the AmericanEconomic Review. The study found that being held in jail while awaiting trial also makes it more likely that, two to four years after an initial arrest, you will be engaged in criminal behavior or unemployed.

A separate study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics showed that while the cash-bail system penalizes poor people, it also discriminates against African-Americans, who tend to be treated more severely than white people by judges who set bail, regardless of the judge’s race.

Two scholars — Will Dobbie, an economist at Princeton, and Crystal Yang, a law professor and economist at Harvard — were co-authors of both studies. Jacob Goldin, a law professor and economist at Stanford, was also a co-author of the firststudy, “The Effects of Pretrial Detention on Conviction, Future Crime and Employment: Evidence from Randomly Assigned Judges.” David Arnold, a graduate student in economics at Princeton, was a co-author of the second, “Racial Bias in Bail Decisions.”

Both studies analyzed the bail system in two counties, Miami-Dade in Florida and Philadelphia in Pennsylvania. By subjecting judicial bail-setting decisions to statistical analysis, the first study found that some judges tended to be stricter in their bail rulings, and some more lenient. Which judge a defendant was assigned to was, for the most part, a matter of luck.

In most court cases, judges, whether lenient or strict, made the same decision as their peers, the study found. All of them set bail high for violent felonies, for example. But in about one-seventh of the cases, whether the defendant ended up detained or released hinged on which judge made the bail determination. Zeroing in on this group of “close-call” cases — in which the leniency of the judge was the decisive factor — enabled the researchers to go a long way in establishing causation in the effects of cash bail on a person’s future.

Consider two defendants with similar backgrounds who were accused of a nonviolent property crime or misdemeanor. By the luck of the draw, one faced a lenient judge and was released, and the other got a different judge who set an unaffordable bail amount. Such an unlucky defendant was detained until trial, typically for about two weeks, the study found.

The researchers then traced the defendants’ lives. The detained arrestee was more likely to appear in court for his trial.

But he was also more likely to be convicted. The study found that in the two counties, being detained before trial increased the chance of being convicted to 58 percent from 44 percent. That’s a big effect and one corroborated by other studies, in settings including New York City and the federal court system.

Moreover, being detained until trial reverberates for years. The study also found that detainees were more likely to commit crimes after release. One reason may be new personal connections made while locked up: Jail and prison are prime networking opportunities.

What’s more, the study linked court records to Internal Revenue Service data for more than 200,000 people. Three to four years after trial, the detained arrestee was less likely to be employed, according to income tax filings.

In the second study, the researchers used the same core data and found compelling evidence of bias against African-Americans in bail decisions. Among the “close-call cases,” judges tended to treat African-Americans more harshly than whites, based on an analysis of the frequency of defendants committing new crimes.

On average, white defendants in this group, who were released before trial, were rearrested for a new crime 24 percent of the time, compared with only 2 percent for African-Americans. In other words, African-Americans who were released before trial were, on average, far less likely than whites to commit crimes, implying that they were being held to a higher standard.

The implications of the two studies are powerful and troubling. Being behind bars while awaiting trial had profound negative repercussions, and they were borne disproportionately by low-income people and by black people.

Several government and nonprofit efforts are underway to reform the bail system. In New York, Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo has proposed ending cash bail for minor crimes. Court rulings have challenged its legality. Nonprofits are posting bail for low-income defendants.

Alternatives to cash bail exist. One method is known as supervised release, a parole-like system that requires people released before trial to regularly check in with social workers. Technological solutions, like electronic anklets that monitor an individual’s whereabouts, are another option. Even sending text-message reminders to show up in court makes it more likely that a defendant will do so. All these options are cheaper than incarceration.

Finding good alternatives to cash bail would be important even if “only” two weeks of freedom were at stake. In fact, the two studies suggest, what’s at stake is an individual’s future. Surely, poverty and the color of a person’s skin should not govern their treatment in the criminal justice system.

Seema Jayachandran is an economics professor at Northwestern University. Follow her on Twitter: @seema_econA version of this article appears in print on March 3, 2019, on Page BU8 of the New York edition with the headline: Consequences of the Cash Bail System

PLEASE contact your state rep by Friday, Feb. 1

Please email the list below of constructive criminal justice reform bills to your state representative and senator and ask them to co-sponsor these bills. When six constituents contact a legislator, they pay attention.

State reps need to decide which bills to co-sponsor by Friday, February 1, so this is an important week. State senators have a little more time.

After the criminal justice omnibus bill passed in April, there is sparse energy for another comprehensive bill. Yet there are many issues that were not adequately addressed by the omnibus bill — including:fully decriminalizing substance use disorders;increasing access to parole;bail reform; and providing better options for young adults who are entangled in the system.

Each of these bills would make our criminal legal system more fair and effective, and is supported by at least one of the organizations that participates in the Criminal Justice Working Group.

Please email the attached list to your state rep and state senator with a cover note asking them to co-sponsor these bills. The bill numbers and sponsors are included in the list to make it easy for them.

Don’t know who your legislators are? You can look them up at https://malegislature.gov/Search/FindMyLegislator

Thank you very much for taking action.

Lori Kenschaft

Mass Incarceration Working Group of the First Parish Unitarian Universalist of Arlington and EMIT member

Constructive Bills Related to Criminal Justice [copy & paste]

January 2019

Each of the following bills would help make the Massachusetts criminal justice system more fair and effective and is supported by one or more organizations that participate in the Criminal Justice Working Group. Participating organizations include the ACLU of Massachusetts, Citizens for Juvenile Justice, Criminal Justice Policy Coalition, Emancipation Initiative, Greater Boston Legal Services, League of Women of Massachusetts, Massachusetts Community Action Network, and Massachusetts Organization for Addiction Recovery. This list was compiled by Lori Kenschaft (lori.kenschaft@gmail.com).

Decriminalize Substance Use Disorders

These bills are based on the premise that substance use disorders should be handled as medical and public health problems, not criminalized.

HD.2727 / SD.1477: An Act Relative to Treatment, Not Imprisonment (Rep. Ruth Balser, Sen. Cindy Friedman). This bill would allow judges to order a person to get help for an addiction, but prohibit courts from sending a person to jail just for relapsing if they are otherwise engaged in treatment. Currently someone who is on pretrial release or probation and experiences a relapse can be incarcerated even if they are actively working to achieve long-term recovery. Incarceration disrupts treatment, endangers recovery, and greatly increases the risk of overdose after an individual returns to the community. It is both unsafe and unjust to require a person suffering from addiction to remain relapse-free or else face jail.

HD.1044 / SD.1479: An Act Ensuring Access to Addiction Services (Rep. Ruth Balser, Sen. Cindy Friedman). This bill would require that men, like women, who are involuntary committed because of an alcohol or other substance abuse disorder be under the care and supervision of the Department of Public Health or Department of Mental Health. Currently the Massachusetts Alcohol and Substance Abuse Center (MASAC) is operated by the Department of Corrections.

SD.1722 / SD.582: An Act to Eliminate Mandatory Minimum Sentences Related to Drug Offenses (Sen. Cynthia Creem, Sen. Joseph Boncore). This bill would further repeal the failed war‑on-drugs policy of mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses. Research shows that mandatory minimum sentences have no real effect on crime rates, that incarcerating drug users and low‑level drug dealers does nothing to deter crime or the flow of drugs, and that Black and Hispanic individuals receive more of these sentences. Mandatory minimums tie the hands of judges and increase the chance that families will be torn apart by incarceration.

Improve Data Collection and Transparency

HD.1780 / SD.336: An Act Relative to Clarity and Consistency for the Justice Reinvestment Oversight Board (Rep. Michael Day, Sen. Joseph Boncore). This bill would expand the data collection and reporting requirements included in the landmark 2018 criminal justice reform bill to include District Attorneys. Without information from prosecutors about charging and diversion, it is impossible to get a comprehensive picture of the criminal justice system to inform future policy-making and ensure fair treatment.

HD.3412 / SD.795: An Act Improving Juvenile Justice Data Collection (Rep. Chynah Tyler, Sen. Cynthia Creem). The Massachusetts juvenile justice system still fails to collect or share many of the basic statistical data needed to understand how the system is operating. As a result, taxpayers are blindly funding a system without adequate metrics to assess its fairness or effectiveness and policymakers are limited in assessing whether what we are doing improves public safety and the outcomes of youth. Massachusetts also has some of the worst racial disparities in the country. This legislation would gather key demographic data at major decision points to better identify and evaluate policies or practices that may inadvertently drive children deeper into the system.

Avoid Excessive Punishment of Juveniles

HD.2800 / SD.1731: An Act to Promote the Education Success of Court Involved Children (Rep. Joan Meschino, Sen. Pat Jehlen). Current law allows a student charged with any felony to be suspended or expelled from school – prior to arraignment or adjudication – without any opportunity for due process in the juvenile court. This bill would clarify that students who are facing discipline under §37H and §37H½ are entitled to all of the procedural protections received by students facing discipline under §37H¾. Requiring additional procedural protections does not prevent schools from implementing serious disciplinary consequences if the principal determines such consequences are warranted. They simply require the school to take steps to ensure that the offense occurred and was committed by the student being disciplined, and to hear the whole story, including mitigating circumstances, before imposing very serious and potentially life-altering consequences.

HD.2888 / SD.2095: An Act Decriminalizing Consensual Adolescent Sexual Activity (Rep. Jason Lewis, Sen. Rebecca Rausch). Massachusetts is one of only four states that criminalizes consensual sexual activity between two adolescents. Most states have “Romeo and Juliet” laws to ensure that these relationships are handled by parents, not judges. This bill would protect teens from criminal prosecution for consensual sexual activity with peers. It would not change the laws that criminalize non-consensual or forcible sexual assaults by youth or consensual activity with a significantly younger individual.

Promote Better Outcomes for Young Adults

These bills are based on the research showing that young adults are rapidly changing, open to influence, and have distinctive developmental needs until their brains fully mature at the age of roughly 25. Massachusetts taxpayers spend a disproportionate amount of resources on young adults in the criminal justice system, and they have the worst outcomes. Studies show that young adults who are handled by a developmentally appropriate system have lower recidivism rates than those in the adult criminal justice system.

HD.2697 / SD.1533: An Act to Reduce Recidivism among Emerging Adults (Reps. Kay Khan & James O’Day, Sen. Cindy Friedman). This bill would infuse developmentally-appropriate, evidence-informed policies modeled after Massachusetts’ juvenile justice system into the adult system to promote positive outcomes for system-involved young adults (under the age of 25 or 26) and increase public safety by (1) individualized case planning, (2) family engagement, (3) access to education, including post-secondary education, (4) abolishing the use of solitary and restraints, (5) community-based pre-release, (6) access to physical, mental and dental health care, (7) prohibiting discrimination against LGBTQ individuals, and (8) prohibiting incarceration due solely to lack of placement by another state agency.

HD.1295 / SD.530: An Act to Promote Public Safety and Better Outcomes for Young Adults (Reps. James O’Day & Kay Khan, Sen. Joseph Boncore). This bill would, over several years, raise the upper age in delinquency and youthful offender cases to include 18- to 20-year-olds. Young people charged with murder and other serious offenses would still be eligible for adult sentencing. This bill would expand the upper age of commitment to the Department of Youth Services for emerging adults (ages 18‑20) to ensure that there is an adequate opportunity to rehabilitate older youth entering the system, including extended commitment with DYS in “youthful offender” cases up to age 23. This bill would help prevent long-term criminal justice system involvement by ensuring that individuals are both held accountable and engaged in the treatment, education, and vocational training that are most effective for their age group.

HD.3449 / SD.1908: An Act Relative to Expungement (Reps. Marjorie Decker & Kay Khan, Sen. Cynthia Creem). In 2018 Massachusetts passed legislation that allowed the expungement of criminal records for individuals whose offense was charged prior to their 21st birthday. While this was an important step forward, the law created significant limitations by allowing only one charge on the record and making over 150 offenses categorically ineligible for expungement. These strict criteria mean that very few individuals are eligible under this law, which intended to help young people access education, employment and housing. This bill would close major gaps in the law by (1) letting people expunge records even if they have more than one charge, (2) permitting the expunging of any juvenile offense except never-sealable sex offenses, (3) preventing all juvenile fingerprints from going to the FBI, (4) allowing juvenile records to be sealed immediately by a judge if there was no adjudication, and automatically once the waiting period expires, (5) treating access to youthful offender juvenile court files the same as delinquency cases, and (6) stopping juvenile offenses from triggering mandatory minimum sentences in later adult cases.

HD.1228 / SD.94: An Act to Prevent the Imposition of Mandatory Minimum Sentences Based on Juvenile Adjudications (Rep. Liz Miranda, Sen. Will Brownsberger). This bill would prohibit the use of juvenile cases as predicate offenses that trigger later mandatory minimum sentences. Youth of color and LGBT youth are disproportionately involved in the juvenile justice system and are therefore especially vulnerable to disproportionate penalties as adults.

Allow Judges to Use Discretion in Responding to Probation Violations

SD.1727 / SD.254: An Act Relative to Probation Violations (Sen. Cynthia Creem, Sen. Will Brownsberger). A judge may suspend a criminal sentence and allow a person to serve a term of probation. An anomaly in the Massachusetts law requires, however, that if probation is revoked due to any violation of a condition of probation, the judge has no discretion but to impose the original suspended sentence, even if the new offense is very minor. This bill would amend the Massachusetts law to, like the current federal law, provide for judicial discretion when incarceration would not be a just and warranted response to a probation violation.

Reduce Recidivism by Better Access to Visits and Calls

These bills are based on studies showing that visits and phone calls help maintain family relationships, reduce violence, reduce recidivism, and promote successful rehabilitation and re-entry.

HD.3011 / SD.2137: An Act to Strengthen Inmate Visitation (Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz, Rep. Marjorie Decker). This bill would eliminate overly broad restrictions on visitation. The present system discourages visitation and makes it easy to lose connections that are important for good outcomes.

HD.3636 / SD.690: An Act Reducing Recidivism and Promoting Family Relationships During Incarceration (Rep. Liz Malia, Sen. Harriet Chandler). This bill would require that jail and prison staff receive training on the importance of visits to those who are incarcerated and the positive benefits of maintaining family ties. It would also require training on how to promote safety and encourage positive interactions with families and other visitors.

HD.3024 / SD.888 / SD.1741: An Act Relative to Inmate Telephone Service for Inmates / An Act Relative to Inmate Telephone Calls / An Act Relative to Inmate Telephone Rates (Rep. Chynah Tyler, Sen. Will Brownsberger, Sen. Mark Montigny). All of these bills would reduce the exorbitant cost of phone calls, which isolates prisoners from their families. SD.888 would provide for free calls.

Regulate the Use of Force

HD.2372 / SD.2050: An Act to Create Uniform Standards in Use of Force, Increase Transparency, and Reduce Harm (Rep. Mary Keefe, Sen. Michael Barrett). This bill would create uniform standards for the use of force in all state and county correctional facilities, including entrance of cell procedures and the use of chemical agents, restraining chairs, and K-9s. It would require uniform standards for reporting on the use of force against individuals who are incarcerated. It would also require all correctional officers to wear a personal audio-video recording device that is activated during planned entrance of cell procedures, emergency entrance of cell procedures, and all other uses of force.

HD.2956: An Act to Reduce Harm by Creating Baseline Standards for Use of Force by K9’s in Correctional Facilities (Rep. Tram Nguyen). This bill would create uniform standards for the use of force by K-9 dogs in state and county correctional facilities.

Increase Access to Parole

These bills are based on research showing that people who are released on parole often have better outcomes than those held until the end of their sentences, and at lower expense to taxpayers. Studies also show that many people “age out” of behaviors that endanger public safety.

HD.3620: An Act Establishing Presumptive Parole (Rep. David Rogers). Currently an individual who is eligible for parole has to convince the Parole Board that they deserve to receive parole. This bill would shift the burden of proof so that the state would have to indicate why an individual who is eligible for parole should not receive it.

HD.1903 / SD.1860: An Act Relative to Parole (Rep. Andres Vargas, Sen. Cynthia Creem). This bill would expand the size of parole board to nine members, to decrease time for decisions. Currently many people wait for months after they are eligible for parole to receive a decision about whether they will be paroled – sometimes until the end of their sentence. This bill would also require at least three members of the Parole Board to have at least five years of experience in the fields of psychiatry, psychology, social work, or the treatment of substance use disorders. Expertise in these clinical fields would help the Parole Board more accurately evaluate prisoners.

HD.154 / SD.533: An Act to Reduce Mass Incarceration (Rep. Jay Livingstone, Sen. Joseph Boncore). This bill would eliminate the sentence of life without parole, as well as all other sentences or combination of sentences that mandate incarceration for more than 25 years. It would require the possibility of parole, and the opportunity for a parole hearing, after 25 years. It would not require release, just a possibility of parole. This change would be retroactive and would apply to those currently incarcerated. Currently, one in eight people in our state prison system are serving sentences of life without parole. People can and do change, especially after 25 years, and those who change should be allowed some hope of not dying in prison.

Protect Voting Rights

Under current Massachusetts law, people who are currently incarcerated because of a felony conviction do not have the right to vote, though their voting rights are returned upon release. People who are incarcerated for other reasons, including pre-trial or after a misdemeanor conviction, retain the right to vote. In many cases, though, people do not realize they have voting rights and/or cannot access voting materials.

HD.1107 / SD.1814: An Act to Increase Voter Registration, Participation, and to Help Prevent Recidivism (Rep. Russell Holmes, Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz). This bill would protect the voting rights of incarcerated people who retain that right. It would require access to voter registration, voter information, and absentee ballots for incarcerated people who have the right to vote. It would also require the education of prisoners, attorneys, judges, election officials, correction officials, parole and probation officers, and members of the public about when voting rights are lost, not lost, and restored. This bill was drafted by the incarcerated members of the African American Coalition Committee at MCI-Norfolk, the state’s largest prison.

SD.25 & SD.26: Proposal for a Legislative Amendment to the Constitution Relative to Voting Rights & An Act Relative to Voting Rights (Sen. Adam Hinds). Together, these bills would restore the right to vote to all citizens who are incarcerated, including those convicted of a felony.

Increase Access to Re-entry Programs

HD.1096 / SD.1178: An Act Relative to Community Corrections: Increasing Access to Reentry Programs (Rep. Frank Moran, Sen. Will Brownsberger). This bill would make all formerly incarcerated people eligible to participate in reentry services at the nineteen existing Community Corrections Centers, which provide assistance with housing, jobs, and treatment for substance use disorders. It would authorize the Department of Probation to allow effective non-profits to offer reentry programs and to separate reentry services from sanctions and corrections locations. It would also require the Department of Corrections and county Houses of Correction to provide departing prisoners with government identification cards and with information about re-entry services.

Reduce Recidivism by Increasing Employment Opportunities

HD.3637: An Act Promoting Family Stability by Further Reforming Criminal Offender Record Information, Increasing Access to Employment and Preventing Unfair Accrual of Debt (Rep. Liz Malia). This bill would increase access to jobs by ending the disqualification of drivers from transportation-related positions based on criminal cases that ended favorably in dismissals and by amending the casino-gaming law to end the disqualification of job applicants based on felony theft convictions (until 2018 the threshold for a felony theft was just $250). This bill would also require that people who are incarcerated be given information about their right to request a reduction in child support orders while they are incarcerated, to avoid racking up massive child support debt that they have no ability to pay.

HD.3635: An Act Providing Easier and Greater Access to Record Sealing (Rep. Liz Malia). This bill would provide for the automatic sealing of records after the applicable waiting period. The sealing process is now done manually for each and every request, and a request has to be mailed or delivered to the Office of the Commissioner of Probation. This change would increase efficiency and benefit many people who are harmed by their criminal records but unaware of their right to seal their records.

Protect Civil Liberties

HD.2759 / SD.1804 An Act Relative to Forfeiture Reform (Rep. Jay Livingstone, Sen. Cynthia Creem). This bill would require that a person be convicted of a crime before the government can take their private property. An independent survey of state forfeiture laws gave Massachusetts an ‘F’ grade in our use and abuse of forfeiture laws.

HD.2726 / SD.671: An Act Relative to Unregulated Face Recognition and Emerging Biometric Surveillance Technologies (Rep. David Rogers, Sen. Cynthia Creem). This bill would establish a moratorium on unregulated government use of face recognition and other biometric monitoring technologies that can screen, identify, and surveil people from a distance without their awareness and without any privacy protections.

HD.1978 / SD.1229: An Act to Protect Electronic Privacy (Rep. Sarah Peake, Sen. Hariette Chandler). This bill would require a warrant for access to information about your cell phone and computer use.

HD.1710: An Act Relative to Access to Justice (Rep. Michael Day, Rep. Marjorie Decker). This bill would ensure that all victims, witnesses, defendants, and people with civil matters in court receive due process and are able to attend court proceedings in safety. Massachusetts courts must be places of redress and justice — for immigrants, and for all.

Abolish parole? WHY NOT?

Former New York City Commissioner of Correction and Probation, Martin Horn has held every job imaginable in corrections: from debating the fairness of a state’s sentencing guidelines to fixing leaky water pipes in aging facilities.

Former New York State Parole Director and New York City Probation Commissioner Martin Horn has proposed abolishing parole supervision and channeling the savings from reduced revocations to provide vouchers for persons on parole to buy their own services and supports.

Horn believes that parole is not particularly good at rehabilitating people on its caseload because parole is about taking risks and government is risk-averse. He reasons that individuals convicted of a new crime during the time they would have been on parole should be given moderate additional punishment, but should not be violated for non-criminal acts.

Give Returning Citizens More Responsibility

By putting programmatic decision-making into the hands of returning citizens, Horn also believes services will flow into the neighborhoods they live in.

Horn’s watershed proposal, and the experience of New York City, force us to ask basic questions about the proper role of government in helping people reacclimate to their communities.

High caseloads, scarce resources and a “trail ‘em, nail ‘em, and jail ‘em” attitude that replaced the Progressive-era’s rehabilitative ethic has rendered community supervision too big, overwhelmed and punitive to succeed.

There is not much evidence that revoking and imprisoning people contributes to public safety or rehabilitation, but we know it has a devastating and disproportionate toll on poor, young men of color. In contrast, recent research by Patrick Sharkey has found that increasing community programs helps improve community safety.”

See more here: https://thecrimereport.org/2019/01/24/do-we-really-need-probation-and-parole/ Learn more about Martin Horn here.

Submitted by Jean Trounstine, Massachusetts activist and author.